It is not often that you come across an artist with a vision as unified as Peter Tyndall. Having maintained a rigorous studio practice for the past 50 years, he is recognised today as one of the leading figures in the development of postmodern art in Australia. Over the course of his decades-long career, Tyndall has exhibited in the world’s most influential institutions and shows, including the 1988 Venice Biennale.

Buxton Contemporary’s latest exhibition marks Tyndall’s first ever major retrospective. Curated by Samantha Comte and Simon Maidment, this survey features over 200 works from the artist’s substantial oeuvre.

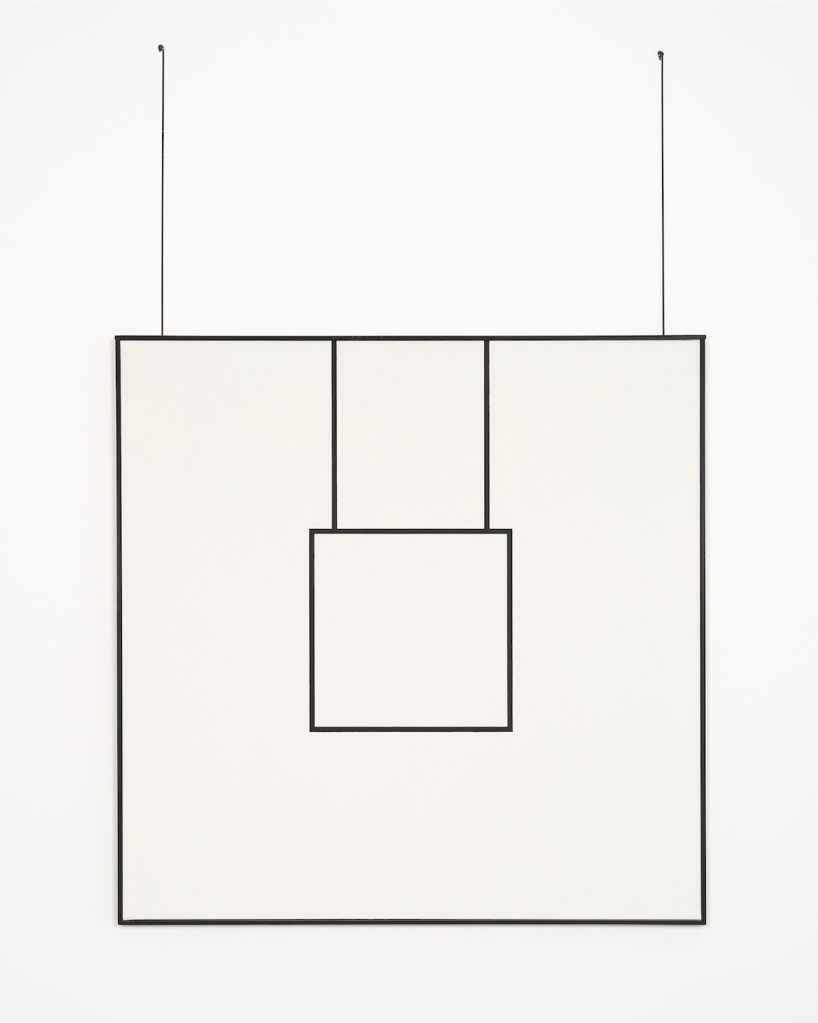

What is remarkable about Tyndall’s practice is that, for 50 years, his output has consistently revolved around a single ideogram: a simple square adjoined by two straight lines. In 1974, Tyndall began using this symbol to express the idea of a work of art. And from that moment on, it became the cornerstone of the artist’s concept-driven practice.

The exhibition at Buxton opens with a work that displays this iconic ideogram in its most basic form. An image of a square with two vertical lines attached to it is painted on a white canvas, which, in turn, is suspended on the museum’s white wall with two hanging wires. It is a radically self-referential work that reveals a fundamental question that can be carried across the entire exhibition: how do we construct meaning in art?

In this opening work, the viewer is presented with two versions of the same thing. We see an image of a painting within a painting. And if we are looking at this canvas as a work of art, how can we, as a viewer, say with any certainty that the ‘real’ artwork is not actually the artwork illustrated within the painting?

It’s a puzzling question that comes with all sorts of metaphysical implications. But it’s the type of question that so elegantly captures the philosophical nature of Tyndall’s practice.

Influenced by his long-standing interest in Buddhist and Zen teachings, Tyndall has consistently approached art-making as a collective endeavour. For Tyndall, we are each sustained by that which surrounds us and that which has preceded us – everything is interconnected and nothing stands on its own.

We see this idea executed with clarity in some of the works displayed in the first floor gallery. In this section, Tyndall draws upon the works of artists who have preceded him, repurposing them in a quasi-Pop art style. There is an appropriated version of Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) as well as two black and white comic book paintings reminiscent of 1960s-era Roy Lichtenstein.

In these works, Tyndall challenges our understanding of artistic originality and implies a spiral of interconnected relationships in which the past is tied together with the present and the present is tied together with the future. It’s a nod to the Buddhist concept of samsāra: the continuous cycle of life, death and rebirth that governs our existence in this world.

Visitors to the exhibition will quickly note that the works in the show share an intriguing detail: they all have the same title.

This is no accident. Since November 1974, Tyndall has been using the same working title to label all his works. It goes like this: detail, A Person Looks At A Work of Art/someone looks at something…

It is an intriguing title because it implies (in the word ‘detail’) that the work is part of something greater than itself. The idea of art as a stand-alone object is negated. But its real innovation comes from the second part of the title, in which Tyndall implicates us, the viewer, into the very act of art-making and creation itself. Here, a person (the subject) looks at (the action) the work of art (the object), and wills it into existence.

For Tyndall, the canvas is the projection space by which things come into being. We can take this idea one step further and say that the gallery is the projection space by which art comes into being.

Read: Exhibition review: Destiny Disrupted

The works in this collection present us with a bold directive: to look beyond the canvas and to consider the work of art as part of something greater. What we see within a work of art is not in and of itself ‘art’; it only becomes art once we perceive it as such. Tyndall takes this idea the furthest in detail, A Person Looks At A Work of Art/someone looks at something… LOGOS/HA HA (The Sword of Manjushri). First staged at Anna Schwartz Gallery in 2000, this work calls upon the audience to play the leading role in its production.

There is a noticeable lack of didactics in the exhibition space itself, which means that some of these ideas can get lost in the sheer mass of works. But I imagine that this is exactly how Tyndall intended for his works to be experienced – free from the constraints of convention and expectation, and sustained instead by our very own personal narratives.

Tyndall reminds us that art and life are inextricably linked. And if we wish to see ourselves and the world in which we live a little more clearly, all we have to do is look.

Peter Tyndall continues at Buxton Contemporary, until 16 April 2023; free.